Blog

An old, sprawling house, empty since Grandma died. During the Cultural Revolution the family had to scrape off all the decorations with a knife and cover the holes with cement. Each New Year they used to gather together to clean the house, it was a festive and happy tradition, with a sad sequel. The house was demolished by order of the government, the land confiscated to make way for a paper factory. The money was divided over the numerous family members, whose xue mai or ‘blood connection’ has been severed now that they have been violently driven apart. In the old days Jane and her family went swimming in the river behind the house, now the water is polluted.

Starting with labor and its need for privacy and darkness, parenting is primal. There’s so much talk about methodology, but we’re animals, relying on instinct. Sure, our kids can take Mandarin, but at the end of the day, we’re just trying to keep them alive. I’m angry that I worry about sending you to school, but at the risk of paralysis, I relegate this fear to a subconscious level. I read that bullet-proof blankets have been invented for school shootings, and I wonder: is this fear more than, equal to, or just different from the fear of mothers throughout history?

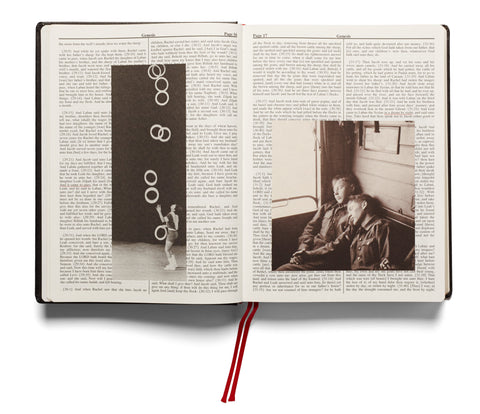

Photography became my life. It has helped me greatly to express my feelings, and to connect with the world around me, when I need it the most. Through photography, I have been able to express what is going on in my mind. Anything that touches me and is important to me makes me want to capture it in a photograph. The world is a loud place and feels overwhelming to me, but my camera helps me to deal with that.

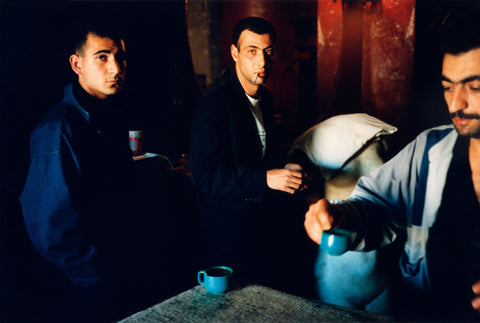

Sharing other people’s homes means negotiating a balance between intimacy and the characteristic eagerness of the photographer. It also means bearing in mind the photographer’s power, taking care to name the people in the photographs and to bring them prints, as well as heeding their wishes regarding public exposure. For instance, she has never published or exhibited a stunning shot she made of a mining woman taking a shower, and recalls a remarkable scene with a mechanical mower, which she could not photograph because the man operating the machine did not wish it.

I realize that the commercialization of the art market is obscene. I understand it must be really difficult for artists who want to have a critical voice. But one must have some kind of a belief. One thing that I mentioned in a piece some time ago, I don’t know if you ever saw it, is that the museums and the artistic institutions can still play a role today. I referred to something that Boris Groys once wrote, that maybe the museums could be the places where one could, let’s say, extract art from the market.

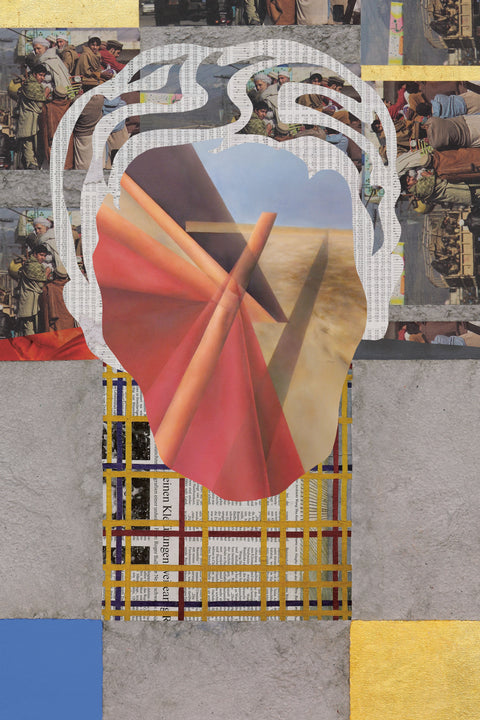

The relations between divine and earthly economies of violence underwent a significant transformation with the emergence of the modern state and its consolidation as a totality (of spaces, people, associations, etc.), a multi-apparatus that strives to control everything it contains and to contain everything it can control. On the one hand, the state has become a potential or actual generator and facilitator of large-scale disasters, and the destructive power of some states has been brought to perfection. On the other hand, the state has also become a facilitator, sponsor, and co-ordinator of assistance, relief and survival in times of disaster.