Blog

Back in 1945, my grandfather disappeared from Gliwice in Upper Silesia along with countless other men. They were taken by train to a working camp in Ukraine. His grave is unknown and all that remains is a small diary he wrote throughout his deportation. In 1978, following a lengthy existential struggle and forced political unemployment, my father left Gliwice with his family to start a new life in West Germany. I understood that my family’s lives had been considerably influenced by forced immigration, and that trains had played a significant role in the process of resettlement.

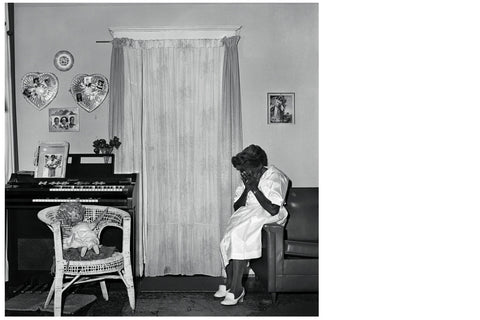

There’s this idea of taking a portrait of someone through their space: Not through the space that they want hidden off, but the space they occupy. Not the ballroom, but the bathroom. This is something you’ve maybe been doing all along. And so when you talk about humans really being the kindling that sets fire to an image, I understand what you mean, but there’s a kind of charge to photographing the small spaces of someone’s life.

The question, the problem in fact, is how to draw a line that encompasses both ourselves and these histories, and yet seeks to claim them in the morbid light that they cast on us all in this place, as inheritors of a dream whose radiance is buttressed by so much blood that the telling of it sickens, withers flesh, prompts an instinctual aversion of the eyes? What is it to want this, if this is America? What is it to want an America that cannot own its genesis, if not the wilful obliviousness of Random Harvest, the sort that obliterates all recollections of the trauma of bloodshed in order to find freedom and love in the hollowed vacuum of amnesia? What sort of freedom would ask of us to forget acts and events such as these, and the sure and certain knowledge that their calculus continues, both at home and abroad? Or, is forgetting in fact the necessary measure of American freedom?

Langton Street, where Delaney lived, was located on the far western edge of the redevelopment area — less than a mile away from the razed central zone. It comprised a mix of small-scale apartment buildings, light industrial businesses, and a few single-family homes. Delaney’s neighbors included families with young children, artists, gay men, retired blue-collar workers, and the owners of assorted types of small, light industrial businesses. While few of them were at imminent risk of losing their homes or commercial spaces to the wrecking ball, they were all feeling the pressures of redevelopment in other, often insidious ways.

Shore’s perspective on vernacular photography is not that of an emulator or appropriator. The apparent legibility and ordinariness of a snapshot are, for him, surface qualities (his brilliantly titled American Surfaces suggests as much). When he set about to interrogate the snapshot aesthetic, Shore remained aware of exactly the things left out of most discussions of the vernacular: photographic technique, presentation and print quality, personal vision.