Popular opinion to the contrary, explicit description does not preclude richness, mystery, metaphor or pathos. Those qualities may well reside within explicit factuality and seem the more cogent for their tie with truth. - Sally Eauclaire, The New Color Photography, 19811

Janet Delaney moved to 62 Langton Street in San Francisco’s South of Market district because the rent was cheap and the location was central. It was 1978, and she hoped the experience would be like living in New York’s SoHo district, where similarly grimy former warehouses and textile mills had recently become home to a growing population of adventurous young artists of limited means, like her. Because South of Market, a part of town that most San Franciscans only drove through on their way to someplace else, had a reputation for being a blighted no-man’s land, even a slum, Delaney was surprised to discover that it was actually a neighborhood with a small but vibrant community of longtime residents and business owners. Relocating there in the midst of a radical urban redevelopment project designed to remake the area, Delaney became active in local efforts to protest the city’s treatment of poor and working class residents, photographing the community as it underwent what was to become its fourth major transformation since the American flag was first flown over San Francisco in 1848.

Before the Gold Rush in 1849, the area now located south of Market Street had been uninhabited. In its untouched state it was an Edenic, if frequently windy and foggy, bayside region composed of tall white sand dunes interlaced with streams and estuaries that had for centuries served as a hunting and fishing ground for the Ohlone Indians.2 Once the hordes of itinerant miners who flooded into San Francisco, the closest port to the gold fields, had occupied all the available space around the center of town, some set up camp in the isolated dunes along the bay. They named the tent city they erected “Happy Valley”, the first of many monikers given to the locale, but the idyll was short lived [fig. 1]. By the 1860’s the picturesque dunes had all been leveled, the estuaries filled in, and the area derisively referred to as “Tar Flat”, after the local gas works had poisoned it with noxious chemical byproducts.3

Largely populated by single male workers, Tar Flat was quickly crowded with boarding houses, pawnshops, saloons and other small businesses designed to serve them. Jack London, who was born there in 1876, called the neighborhood “South of the Slot”, after the channel housing the streetcar cable that ran down the center of Market Street, writing of its character, “North of the Slot were the theatres, hotels and shopping districts, the banks and the staid, respectable business houses. South of the Slot were the factories, slums, laundries, machine shops, boiler works, and the abodes of the working class”.4 The economic divide demarcated by Market Street that London described would remain in place for over a hundred years, as it does today in certain sectors.

The second transformation of the area followed the catastrophic earthquake of 1906. With the exception of a few mason-built public structures that were heroically saved by the people who worked in them, South of Market was almost completely leveled in the gas-stoked inferno that followed the temblor5 [fig. 2]. More buildings were felled and more residents perished there than in any other part of the city, and it would be the last section to be completely rebuilt. Less than 30 years after the quake, the area’s largely poor and working class population was devastated yet again, this time by the Depression. Fortunes rebounded briefly during the ship-building boom brought on by World War II — the area’s third major transformation — but after the demand for armaments ceased South of Market slid back into its Depression era state, a “Skid Road” inhabited by an aging population of working men, many of whom were unemployed, disabled, and without a safety net.6 Actively perpetuating the area’s reputation as a dangerous slum, the city’s largely conservative local newspapers ran staged photographs that sensationalized the reality of life in the neighborhood, stoking the fears of middle and upper class San Franciscans [fig. 3].

By the 1950’s, South of Market remained the only central zone in the city where significant expansion was both physically and politically feasible.7 The fact that a relatively small and seemingly disunited population was the only obstruction to the scheme made the area an attractive target for urban renewal, as the city’s powerbrokers expected little civic resistance to the razing and reconstruction of a neighborhood that few San Franciscans recognized as one. While the push to redevelop South of Market was often framed in the press as socially beneficial slum clearance, the harsh reality, as the head of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency once baldly put it, was that the “land [wa]s too valuable to permit poor people to park on it”.8

The political will to implement a formal redevelopment plan was finally brought to bear in the late 1960’s. In the first phase, the city took possession of many of the area’s residential hotels, which officials willfully neglected once under their care, allowing them to descend into utter decrepitude, refusing to make repairs or upgrades, and eventually condemning them.9 The residents, a large percentage of whom were senior citizens, were summarily evicted and few were offered replacement housing. Their plight was poignantly documented by photographer Ira Nowinski, whose work, published in 1979 as No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly, influenced Delaney’s development of her own politically inflected South of Market project10 [fig. 4].

Most of the residential hotels in the central redevelopment zone had already been leveled, and over 4,000 residents and 700 small businesses displaced by the time Delaney moved South of Market.11 The succeeding phases of the project had only just begun, however, as lawsuits brought by the previous occupants of the hotels and other groups organized in opposition to the “Manhattanization” of San Francisco had halted construction for many years.12 In the interim, the razed lots lay fallow, serving either as temporary parking lots or sitting empty and fenced off, eerily appearing much as they had in the years following the 1906 quake [fig. 5].

Langton Street, where Delaney lived, was located on the far western edge of the redevelopment area — less than a mile away from the razed central zone. It comprised a mix of small-scale apartment buildings, light industrial businesses, and a few single-family homes. Delaney’s neighbors included families with young children, artists, gay men, retired blue-collar workers, and the owners of assorted types of small, light industrial businesses. While few of them were at imminent risk of losing their homes or commercial spaces to the wrecking ball, they were all feeling the pressures of redevelopment in other, often insidious ways. The character of their neighborhood had been irrevocably sundered by the demolition of the hotels and businesses nearby: the population had decreased precipitously, public services had declined — many believed purposefully, as another means of driving poor residents out — and rents had started to rise in the first wave of gentrification.

The period was a transformative one for Delaney, as well. Soon after she moved to Langton Street she entered the graduate program at the San Francisco Art Institute.

At a time when many of her contemporaries were constructing set pieces in their studios or experimenting with alternative photographic processes, Delaney chose a different path. “I didn’t go in for any of that”, she says, “I am from Compton”, an austere working class section of Los Angeles.13 She was drawn instead to the urban environment, and when she moved to her new flat, she and fellow photographer Catherine Wagner began shooting at construction sites in and around San Francisco, including the enormous Moscone Convention Center complex then being built South of Market.

It was only when Delaney left the construction site behind and began photographing her neighbors in their homes and places of business that form and content began to coalesce in her work. In retrospect, she believes this evolution came about as a result of having recently spent six months living and traveling in Central America, where she gained a newfound understanding of the interconnection between politics and economics after visiting the war-torn countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. She likens her political education to her concurrent study of Spanish, where, as she explains, “you come to understand grammar better than you do in English because you actually need to take it apart piece by piece in order to comprehend it”.14 Although she had made photographs on her trip while “learning about revolution”, they were, like the pictures she subsequently took at construction sites, formalist compositions that did not reflect her political sensibilities [fig. 6]. Upon her return from Central America, Delaney read the work of Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula, whose reframing of the traditional documentary approach into a more engaged and activist practice resonated with her as she became aware of the economic and political pressures then being exerted on her neighborhood.

Delaney characterizes the photographs gathered in this volume as an attempt to “name” South of Market, to call attention to the fact that hardworking people actually lived there, and to document the human cost of redevelopment. The large format work was one facet of a larger project she conceived with her friend and fellow photographer, Connie Hatch, under the name “*D’Art” for “Documentary Art”, for which they each made their own very different photographs [fig. 7]. Delaney and her roommate, Laura Graham, then a film student at San Francisco State University, also shot Kodachrome slides and recoded audio interviews with their neighbors on Langton Street. Their audiovisual project was shown in various neighborhood organizing events, and eventually presented in the 1981 exhibition “Form Follows Finance” at San Francisco Camerawork, an artists’ space then located South of Market.

Funded largely by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the project was designed to integrate daily life and politics with art, and involve other South of Market residents in the process. Delaney and Hatch aspired through the work both to rally their neighbors to collectively organize around the “goals of rent-control, anti-speculative legislation, adequate low-cost housing, local control of development, guaranteed maintenance of city services (police and fire protection), and responsible leadership”, and to “counter the flat, homogenized generalizations that corporate interests and our money-elected ‘representatives’ use to sell of our lives and homes as ‘bums in slums’”.15 San Francisco, they contended, was losing its diverse character in the process of redevelopment, threatening to become a “formless, faceless Everycity”, a place that was too expensive for working class people to live [fig. 8].

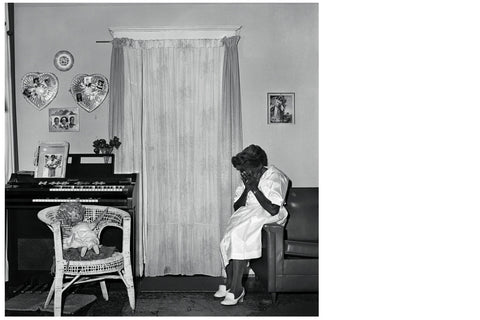

Although their concerns were presented in the first person plural, “We do not need to be replaced by a plastic caricature of ourselves”, they wrote in a handout printed for the exhibition, “sanitized for the bland corporate palates of Dallas, Tokyo and Wall Street”, the work was intensely personal for each of the participants. “I was never neutral”, says Delaney. It mattered who was behind the camera. “I lived in the neighborhood”, she explains, “I was not coming from outside and imposing ideas on a place, and since I used a view camera, every photograph I made was an agreement between my subject and me”.16 That connection is palpable in the portraits, where her sitters, many of whom she knew, are portrayed with dignity, and the places where they lived and worked shown as functional and productive, if a little homely and worn. These average working-class San Franciscans had little recourse to address the ways in which redevelopment was impacting their lives, and by interviewing them and exhibiting their portraits, Delaney sought to provide them with a platform for engaging in the debate over the future of their neighborhood.

Today, Langton Street embodies the changes that have come to the area in the wake of redevelopment and gentrification. Delaney and the people she photographed have long since moved away, and the once stark street is now lined with blooming plum trees that shade luxury cars belonging to current residents. A block away there is an upscale wine store, a third generation coffee roaster, and a trendy restaurant featuring “locally sourced” California cuisine. The transformation is even more total in the central part of South of Market, where once vacant lots are filled with luxury hotels, museums, public parks and shopping centers. Young tech workers, international tourists and conventioneers have replaced working class families and the elderly poor. For those San Franciscans who remember the pawn shops and residential hotels that filled this area in the 1950’s, or the trash strewn wasteland the neighborhood became in 1970’s following their demolition, it can be disorienting to sit in verdant Yerba Buena Park at lunchtime surrounded by office workers lounging on the grass and gaze up at the forest of glass towers around it. Knowing how much was lost in the process of redeveloping South of Market, it is easy to feel conflicted about what has been gained.

While an understanding of the socio-economic history of San Francisco would certainly provide viewers with a richer understanding of these photographs, it is not required in order to appreciate them. In an effort to “seduce” viewers into taking a longer look at her subjects, Delaney purposefully broke from the hoary traditions of documentary photography, making beautiful color pictures that describe her subjects, rather than grim black-and-white ones that proselytize for a cause. Thus, the individual pictures in this volume can be enjoyed both as part of a larger story with a political message, as well as on their own for their luminous beauty, the quality of the light depicted in them, and the photographer’s keen attention to gesture and detail. Ultimately, Delaney’s sensitive and humane portrayal of her neighbors, their homes and their environment transcends the time and place in which the pictures were made.

Notes:

1 Sally Eauclaire, The New Color Photography (New York: Abbeville Press, 1981), p. 161.

2 Notes from “Historic Context Statement”, June 30, 2008, prepared for the City and County of San Francisco by Page and Turnbull, Inc. p. 16.

3 Anne B. Bloomfield, “A History of the California Historical Society’s New Mission Street Neighborhood”, California History 74, no. 4 (Winter, 1995/1996), pp. 372-376.

4 Jack London, “South of the Slot”, Saturday Evening Post, May 1909.

5 Bloomfield, p. 384.

6 Hartman, p. 58-60.

7 Catherine Hoover, in Ira Nowinski, No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly (San Francisco: Carolyn Bean Associates, 1979), p. viii.

8 Chester Hartman, City for Sale: The Transformation of San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), p. 19.

9 Bloomfield, p. 391.

10 Ira Nowinski, No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly, Introduction by Catherine Hoover, Afterword by Peter Patrick Mendelsohn (San Francisco: Carolyn Bean Associates, 1979).

11 Hoover, in Nowinski, p. ix.

12 Ibid., p. x.

13 Interview with author, December 16, 2012.

14 Ibid.

15 Announcement for “Form Follows Finance” exhibition at San Francisco Camerawork, 1982.

16 Interview with author, op. cit.

Figure illustration credits:

Fig. 1 SF Images Collection, sfimages.com

Figs. 2 & 3 Collection of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Library

Fig. 4 © Ira Nowinski

Fig. 5 Collection of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Library, © Bill Koska

Fig. 6 © Janet Delaney

Fig. 7 © Connie Hatch

Fig. 8 Collection of Janet Delaney

Text 'Janet Delaney: South of Market' by Erin O'Toole from 'South of Market' by Janet Delaney, published October 2013.