AS I’ve struggled to talk about my work this time around. Maybe I’ll get my banter together over time. But I really don’t have it together now.

HY What do you say when someone asks?

AS That’s what I’m struggling with. I can give a super-long answer. But the short one that I’ve been giving – portraits and interiors wherever I travel: I can feel how unexciting it is. It’s just not sexy. Whereas if you say something like, “I’m traveling along the Mississippi River,” people get it. They can hang onto that.

HY I think all visual artists these days are more or less expected to have some sort of prepared statement.

AS I’ve always liked the accessibility of my work, that people are let into it pretty quickly. Part of talking about it might be for sales, but it’s more about getting people engaged with the work. They’re related, I suppose. It’s like being on a book tour. You have to say something.

HY Yes, but it’s a little different. Because the writer’s medium is words. So you should be able to use words to describe to some extent what you’re doing. Yes, the work should speak for itself, and yes, it stands alone as its own being. There is no amount of explaining you can do that will ever substitute for the experience of reading the book and having a reaction. But I don’t know of a single author who at some point has not had to explain or defend with language their work, which is also of course created with language.

AS Right. But I think there’s a difference between the novel and poetry. So if you’re asked, what is your latest book of poems about? “Well, it’s about, like, light and birds and...”

HY Yes, yes, you’re right.

AS And I think that’s what is happening with me a little bit. I’m on the poetic side of the spectrum. It’s a little less driven by narrative.

HY Do you think part of the difficulties you’ve had explaining the work are related to the sort of—I don’t know how you want to characterize it—but the crisis of art-making that you had before you began this series? And will you talk a little bit about that?

AS Oh boy.

HY It does seem central to the creation of this body of work.

AS It’s true. Yes, it’s the basis of everything. I just worry that this story has become a little self–indulgent.

HY I found it fascinating.

AS Well, a few years ago I started meditating. It wasn’t a huge part of my life. It was just interesting to watch how my brain worked. But I didn’t feel particularly changed. And then I had an experience on a trip to Helsinki. I was meditating on the plane. Then when I landed, I went for a long walk and sat by a lake and meditated. I’m sure the jet lag was a part of this, but I ended up having a full-on mystical experience. The only way to describe it is to say that I suddenly understood that everything was connected. I felt it in a deep and profound way. This changed everything. The next day I had to give a lecture about my work. I stayed up all night rethinking everything about what I do. Photography, for me, has always been about separation and this feeling of social distance that I have. But if I know that everything is actually connected, even if I can’t experience it all the time, aren’t I just promoting or reinforcing distance with my work? So not long after this, I stopped photographing people. I stopped traveling and just stayed at home. I was completely content to give up the path I had been on for all those years. I was just so happy sitting around looking at the light. A year went by of doing this.

HY Were you photographing the light or just experiencing it?

AS Sometimes I’d photograph, sometimes not. I have an abandoned farmhouse on a little piece of land that I’d purchased years before. I started going there to just experience the weather and the light. Sometimes I just read. I tried to never have an intention to produce anything. If it happened, it happened. Then a year went by and I realized, wait a second, I have to work. I decided to start traveling and photographing again, but I thought, well, I’m going to do it in a different way. When I photograph people, I want to find a new way to engage with them. Where it’s not driving around, snagging people, talking them into stuff they don’t want to do.

HY Is that how it felt? Is that how you experienced your earlier series? You make it sound so predatory in a way.

AS There is something predatory about it. It’s not like I didn’t get people’s permission. But there’s a power dynamic at play. Avedon talks about this all the time. In the end, the photographer has the power.

HY I wonder, did you feel you were looking for a kind of humility? Or did you just feel that you wanted something to be corrected?

AS Maybe it’s a correction. When I started as a photographer, I was so nervous photographing people. That made the playing field more even. But as the years went by, I got more professional about it. I wasn’t as nervous. There was this sense of like, here is Mr. Hot Shot photographer coming in. I can handle this situation. Which is definitely different from how I started. After all of that meditation, I thought: Why am I doing this? What value is it to others? I had to figure out how to photograph people again. I did an experimental project at Fraenkel Gallery in which I spent a lot of time one-on-one with people in the gallery space. Sometimes we’d take pictures of each other, but we’d also just play and hang out. The choreographer Anna Halprin wanted to do one of these sessions with me, but she was 97 and too frail to come to the gallery. So I visited her home in Marin. I photographed her in a way that I have always photographed people – with a certain amount of distance. But it felt different. It felt like I had come back to something. Or slightly purified the system.

HY Why?

AS I just felt like a younger photographer; like I’m just taking pictures. This is why it’s hard to talk about this work. It’s like Photo 101. I’m just spending time with a person taking their portrait.

HY What did you have to unlearn?

AS That’s a good question. Instead of getting the subject to do something for my project, maybe it’s more about taking what’s there and having an encounter and having it work or not.

HY Did you feel disarmed?

AS I wouldn’t say disarmed. No. I felt comfortable. I felt like I wasn’t abusing anyone.

HY This is the fundamental question that everyone who photographs people has to ask themselves or should ask themselves. Is there something fundamentally exploitative about photographing people? Do you ever feel you’ve been?

AS Yes. Oh, for sure. Yeah. Absolutely.

HY Why?

AS Because I’m using people for my purpose. There are different kinds of exploitation, different degrees of it. I don’t think mine has been the most severe. But I definitely have an awareness that, yeah, I’m using people. I’m sure that writers struggle with this. I’m sure even figurative painters struggle with it.

HY Was Arbus ever exploitative?

AS Oh, yeah. But she was also a huge influence. My earliest pictures didn’t have people in them at all. Then I looked at Arbus. There’s so much power. And that’s how I thought of people in my pictures – they’re like the gasoline. The power is undeniable. I originally struggled to get that fuel into the engine. But once I did it started to drive everything. And then at a certain point I realized that I’m not taking these people into consideration. Or not enough consideration.

HY Why do you think people agree to be photographed?

AS People like to be acknowledged. Why do people want to be on social media? They want to have an identity and presence.

HY Especially with “Sleeping by the Mississippi,” there were some people where you look at them as a viewer and you just think, no one has asked to see them in years. And so the first way they’re being seen is in a way that opens them to ridicule to some extent. But yet also honors them and memorializes them to a certain extent.

AS Right. It does both of those things. I mean, usually, the process, the experience of approaching a person is very positive. It’s really the part after that I worry about. Most people don’t understand photographs on a wall in a museum. That’s for paintings. They just don’t get it. All of the shoots in this series were set up in advance. People knew more about what they were getting into. They could go online and read about me and figure out the whole thing. It’s more of an even playing field. Take you, for example. You’re a person who definitely understands photography and how it works. We didn’t know each other, but I thought there could be a connection on some aesthetic level. But I could feel your apprehension to being photographed. You stated it, but I could also feel it. I wasn’t interested in getting in your face or having you take off your clothes. That’s something that’s different for me now. Because I know how to manipulate a situation.

HY But could you have, do you think? Do you have those skills?

AS I really think I do.

HY Really?

AS Yeah. A week ago I was invited to take a picture in someone’s old mansion in Salt Lake City. The owner told me that there was a ballroom on the third floor. But then he said his wife didn’t want me to photograph there, didn’t even want me to see it. I know I could have gotten in there if I wanted to. I just don’t feel pushy in that way anymore.

HY If it had been five years ago, would you have pushed?

AS Oh, totally. In a second. Yeah, yeah. I would have been in there. In fact, that would have been my only goal.

HY Is it a different kind of respect for the people? Or is it almost—is it sort of a challenge to yourself?

AS I suppose part of it is respect. But I also have a sense now that it doesn’t matter as much. Enough is enough with the ego gratification.

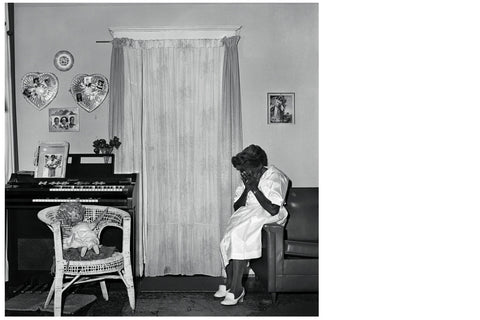

HY Some of the most intimate and the rawest photographs in this series are of spaces. There’s this idea of taking a portrait of someone through their space: Not through the space that they want hidden off, but the space they occupy. Not the ballroom, but the bathroom. This is something you’ve maybe been doing all along. And so when you talk about humans really being the kindling that sets fire to an image, I understand what you mean, but there’s a kind of charge to photographing the small spaces of someone’s life. Is that something that you consciously decided to do with this series?

AS When I started this project, my only intention was to spend time with another person in a room, any room. But after I photo- graphed Anna Halprin, I decided it should be in the subject’s home. This makes them more comfortable. It’s also more stuff to help reveal what might be going on inside of them.

I started thinking about Message From The Interior by Walker Evans. That book only has twelve pictures. They’re all interiors and only a few of them have people, but there’s so much to look at. When I was in high school, I used to deliver Chinese food. I loved that moment when the customer opened the door and I could peek into their interior world. It always felt magical and mysterious. Being a photographer is an excuse to invite myself inside and look around. Sometimes I wish I could just look at the person in the room without ever talking.

HY The poem from which you found the title for this project [‘The Gray Room’ by Wallace Stevens] is about a fundamental distance between the speaker and the subject. And an elemental connection between the two.

AS That poem makes so much sense to me. This is how photography works – this appreciation of all these surfaces, all this beauty. But you can’t quite get inside. It’s about making do with that.

HY And in a way, it’s a very beautiful celebration of the limits of this medium. And I suppose an honest admission that as much as we think photography—and, let’s say, especially portrait photography—captures something, it does, but it doesn’t capture everything. Nor should it be expected to.

AS There’s a shared solitude.

HY You mentioned Peter Hujar and Nancy Rexroth in an e-mail. And I know that you’re a great admirer of Hujar, as am I. Why?

AS Hujar’s influence was like a spiritual aura hovering over this work. He had this incredible intimacy in his pictures. An interiority about them. But also an ability to just make pictures. That was the feeling that I wanted. I didn’t want to try to connect all the dots into a grand narrative. I just wanted to make photographs that were loving and affectionate and tender.

HY I don’t know if you saw the show that Jeffrey Fraenkel held [at his gallery in San Francisco] a couple of years ago of Hujar’s work.

AS I didn’t. No.

HY It was a really beautiful show. It wasn’t that large. But he curated it very beautifully; the pairings were very good. There was this one couplet of the famous picture of David Wojnarowicz with the snake. And next to that was a lesser-known picture of a dark, roiling sea. And then next to that was one of his beautiful horse pictures. And then next to that was a sink with a clutter of objects in and around it. You don’t think of Hujar necessarily as an object photographer. Certainly someone like Arbus was only a portrait photographer. Or at least most prominently. And yet many of his works, you’re right, had that same quality. He was able to somehow suffuse them with the same kind of intimacy as if they were portraits. I think what I have found that I respond to in his work as I look at it more and more is that there’s a mutual respect that runs through everything. When it’s a picture of a horse or a picture of a disabled child or a picture of a former lover. And that kind of graveness, that gravity, is really I think what unites them for me.

AS The word that I would use for Hujar is tenderness. That’s the feeling that I get from Hujar over and over again. No matter how sexualized.

HY Yeah, me too. But then Nancy Rexroth is a very different kind of photographer.

AS Very different. Nancy Rexroth is someone that I see as quite removed from the world. She and I have corresponded over the last few years, but we’d never met until I took her picture. I always imagined her living in an all-white room on the second story of an old house like Emily Dickinson. It was so surprising to see her living in a crammed apartment bursting with color in Cincinnati. But there was still something reclusive about her place.

HY I thought of her when you were talking about light and watching light.

AS When I think of her, I imagine her alone in a room, dreaming about her childhood. And when I think of Hujar, I think of him in a room with another man looking at him tenderly. So they’re two very different photographers. I’m probably some mishmash of both in a way. With other stuff mixed in, too. I don’t photograph people I know. The more I know you, the less likely I am to take your picture.

HY Because you just can’t see anymore? Or you can’t…

AS I don’t understand it. I honestly don’t understand it. It just doesn’t work. I have to get on the therapist’s couch.

HY What is the most intimate moment that you have when you’re making a photograph? Is it when you’re behind the camera itself?

AS Good question.

HY While you think, I’ll talk. When you were photographing me, I thought a lot about this. We had talked about the power imbalance of being the subject and the shooter beforehand. What I remember about the experience was that it was a very womb-like experience. You were literally hidden, shrouded. You were almost in a supplicative posture, I felt. You were enthralled to the machine. And all I had to do was sit still, which wasn’t very difficult. But what you had to do – I suppose what I’m trying to say was it felt like you were being controlled both by me, the subject, and by the camera itself. I think you’re also very... you have a lovely, soft voice. You’re a very reassuring presence. But I was reminded in those moments of the kind of humility it takes to be crouched in an uncomfortable position beneath the hot piece of cloth waiting for the eye of the camera to do what you wanted it to do. So I understand that in the moments before you get behind the camera, there is a sort of dance, there’s an exchange, sometimes more manipulative than others. But once you get behind the camera – and I know people disagree with this – I felt you were disempowered rather than empowered. I mean, I thought of how Arbus always held her camera at her chest. And shot from there rather than up against her eye. And in that sense, it was a restoration of power. She was able to talk and look the subject in the eye while at the same time doing something they couldn’t see. She regained control of the machine. But when you were looking into the machine—I don’t know. You give up something of yourself as a human to the machine. That makes you less powerful, I always think.

AS So that moment, the moment of being under the dark cloth looking at the person is incredible. It’s really satisfying. And this is simply a technical matter. But there’s this anxiety that’s caused by that moment when I have to take off the dark cloth, put in the film, and take the picture. And all the possible things that I could lose. I’m always panicked about that. But the looking is really something. It makes me think about the idea of Zen photography. If I were a Zen photographer, I would just look through binoculars. Binoculars are amazing. Because you’re thrown inside the image. And that far away thing, you can almost touch it.

Conversation from 'I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating' by Alec Soth, published March 2019.