Blog

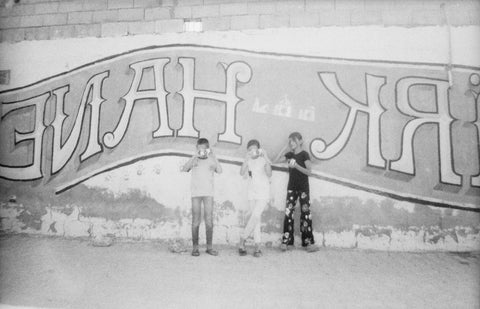

Each time I begin working with a new group of children, I encourage them to take their cameras outside and explore their surroundings and imaginations. The children create stories, play out scenes, and really explore their imaginations within the space of the frame. I see how photography opens up a world of spontaneity, fun, and magic. These photographs show the world of the children as they truly see it: punctuated by play and surprise.