Ahead of the launch of her new book The Shabbiness of Beauty by Moyra Davey & Peter Hujar, Moyra Davey talks us through some of the books she has been reading and enjoying recently.

Sometime in early 2019 Kim Bourus invited me to her gallery, Higher Pictures, in Manhattan, to show me a book by Susan Lipper titled Grapevine, a classic I’d never laid eyes on, and Kim had a hunch it was my kind of book. Photographed in stark black and white with a flash-mounted Hasselblad, Grapevine chronicles scenes from daily life in a small, rural enclave in West Virginia.

I heard Lipper on Jordan Weitzman’s photo-centered podcast Magic Hour, giving the back story, talking about driving around the region for days, ever preoccupied with gas and food and lodging, in search of a subject. Eventually a local shopkeeper mentioned something of interest in an area Lipper later came to name Grapevine, and that is how the project, collaborative and semi-fictional, began. Her subjects are rifle-toting men with worked, sinewy muscles and scarred bellies, and women and children in domestic settings: in one memorable photograph a baby in a bathtub reaches for the water spewing from the faucet, but what it does not see is that Lipper’s flash has transformed the liquid jet into jeweled, cubist crystals.

What I admire in Lipper’s approach is the winding but persistent drive and appetite to search out the thing that was only an intuition. Several decades later Justine Kurland loaded her small son and a 4x5” camera into a van and drove west, and likely did not know what she would find either. Highway Kind, filled with trains and vistas and nomadic peoples surviving off the land and living in ravaged, exurban spaces, is the resulting book.

Lipper has produced a trilogy of the American land and her movements through it over three decades. The final series and book is Domesticated Land, photographed in the bleached white heat of the California desert. Glaringly bright and silvery, the photos are printed at the outer threshold of lightness and visibility. I find pleasure in teasing out their evanescent tones, as I do in deciphering

Roy De Carava’s prints, where it is the blacks that are saturated to the outermost limit of readability. One of the last shows we got to see in New York before lockdown was Roy De Carava's ravishing survey of vintage prints at Zwirner gallery in Chelsea.

In the summer of 2020, Riverside Park became a refuge for residents of my Washington Heights neighborhood. People played sports, worked out, cooked food, celebrated birthdays, swam, boated, did yoga, listened to music, played cards, danced, made out, slept, meditated – in short, much human activity that had formerly taken place indoors was now happening in the park.

For almost ten years leading up to 2020, Irina Rozovsky ventured into Brooklyn’s expansive Prospect Park, often at sundown, and photographed in the soft, golden haze of the magic hour. Her book In Plain Air is dedicated to Frederick Law Olmstead, who designed both Prospect and Central Park, and indeed there is a languid, 19th century feel to some of these pictures of families and couples and friends strolling by the water, fishing, boating, drinking a glass of red wine, engulfed in swirling smoke, or embracing on the grass. Some of the compositions plausibly invoke La Grande Jatte or Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe.

In one photo, distinctly of our era, low, twilight sun illuminates a human-animal dyad: nestled at the trunk of a large, patchy elm tree, a brown-skinned man with cropped, dyed blond hair fondly cradles his red-nosed pit. The dog’s pink tongue hangs out, its pale eyes are the same color as the man’s hair, its coat matches the tree bark, and its claws are as long as human fingers.

There is a strong animal presence in Adam Pape’s Dyckman Haze, a black and white photo book set largely in a nocturnal Riverside Park, a mere mile or so from where I live. Fluffy, long-haired skunks with glowing eyes cavort in lamplight, a raccoon finds sustenance in a trash bin, and large dogs commune with each other and with humans. This book is about the secrets of the night, about bodies, mostly young, hormonal, hirsute and playful, about hanging out, making out and getting high. It is a perfect, gorgeous book, with a mere one line of text telling us when and where the photos were taken (2012-18), a book that constructs and mythologizes its milieu and its inhabitants, in a way similar to Tulsa or The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

Dyckman Haze has a special spine that allows it to lay perfectly flat, something I’m always partial to in a photo book, and there is a slightly old-fashioned look to the offset print quality. The most spectacular spread shows two women, the one on the left in medium close-up has her head thrown back and her features are partially obscured by prolific curls of white smoke that take up nearly a third of the picture frame; on the right-hand page is a more tightly cropped woman in profile, she has a pensive, resolute look, but any doubt conveyed by her posture is bellied by the upsweep of a thick, platinum mane in which swirling strands of stray hair catch the light.

I’m nearly out of space, but I’d like to end with a shout out to Sergio Purtell’s sensuous Love’s Labour, a delectable book full of the kinds of photos that lure your eye to travel to the edges of the frame and back, and to marvel at all that has been contained therein: bodies at rest and in motion, birds in flight, statues come alive, all shot in Europe in silvery black and white in the summers of the late 1970s through the mid 1980’s, when Purtell would purchase a plane ticket and a Eurail pass, and as an exiled Chilean, move about freely and catch glimpses of his past.

And a final shout out to the labor of love that is Deanna Templeton’s passionate book What She Said, with its pink linen cover, and facsimile reproductions of the pink-ruled pages from her teenage diary, replete with the usual self-loathing, but also copious lists and commentary on the bands she saw night after night, drugs taken, lies told, spelling be damned, nothing to get in the way of the spontaneity and vivacity of her recordings. But this is not even the main attraction. The substance of What She Said are the dozens of portraits of teenage girls and young women – goths, punks, metal heads – sweet youthful faces and bad-asses of every persuasion strutting their stuff, or just quietly and openly staring back.

Mentioned books:

Susan Lipper, Grapevine (Distributed Art Pub Inc)

Embossed bare board hardback

24 x 27.1 cm,

96 pages

€40 £35 $45

Embossed linen hardback with tip-in

19.5 x 24.5cm, 168 pages

€45 £40 $50

Add to cart

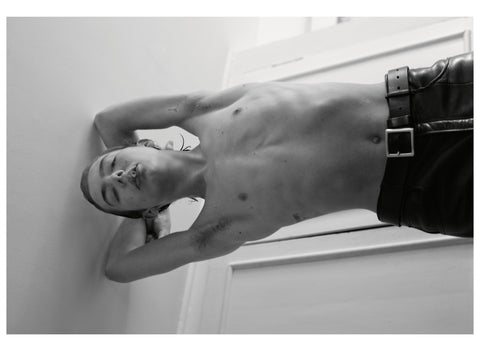

The Shabbiness of Beauty is a visual dialogue that crosses generational divides with the easy intimacy of a late-night phone call, with little-known, scarcely seen images from Peter Hujar’s archives set in dialogue with Moyra Davey’s photographs, forming a visual exploration of physicality and sexuality that crackles with wit, tenderness, and perspicacity. With a newly commissioned text by poet Eileen Myles.