Liz Jobey: When you look back across the range of your work. How do you think your photography has changed over those years?

Hannah Starkey: I suppose it’s less surface, more psychological. It’s as much influenced by what I feel as what I observe. So in that respect, the pictures are more about the interior life than the exterior. How do you picture an interior physiological truth in a photograph and make it accessible?

Does this have more to do with how you’ve changed as a woman, or as a photographer?

Both. Because the longer you are a photographer, the more efficient you get.

Efficient? That’s an odd word to choose.

Well, you have probably honed your brain in a way that’s very efficient at making pictures. I know this might come across as ego—it’s not—but for me, my photography has got better. When I look back on it in my twenties, it seemed so generic: coming up with a brief, fulfilling the brief, exhibiting the pictures. Whereas now my work comes much more from lived experience

But I don’t think my pictures have changed fundamentally because they are how I see. I look for things in the world that I know will photograph particularly well and they’re part of my visual language. For example, that might be reflections, or mirrors, something fluid. I’m always looking for ways to create movement and depth in the frame. You know, surfaces and shapes that gives it an extra layer of abstraction. If you think about a photograph as being mute, two-dimensional and static, then I’m trying to counteract that: to counter what’s expected from a photograph so it becomes something other than just a photograph on a wall, it can become an experience, in a way.

What about the subject-matter. Has your approach to that changed, too?

I used to be far more specific in my mind about the character I was looking for, but in recent years, more often than not, my breath has been taken away by a woman who’s walked past me or I’ve seen in the street. I actually go around pointing these women out to my daughters when we’re driving. I’ll go, “Gosh, she looks good.” You know, because I’m trying to articulate to them that looking good is also a feeling.

This might sound pretty simplistic, but there’s something about when you see a woman in her everyday, just doing her own thing, maybe on the way to work, and there’s something about her self-confidence, not necessarily her visual attraction, but her energy, that you just want to capture, You want to take it and be able to express it in a picture. Maybe that’s what my pictures are doing, reflecting what I am engaged in as I move through my own life. As I age I’m more aware there’s some-thing else going on that as human beings we read as being attractive that’s not just the surface. This doesn’t make it easier to explain yourself to strangers in the heat of the moment! I have to run after them and go, “I’m really sorry but there’s just something about you I want to capture in a photograph that I can’t put my finger on yet! …”

So how do they react?

Actually it’s quite nice, because they’re all women, so effectively what I’m doing is running around the city stopping random women, telling them they are amazing. You know, they are random acts of complimentary kindness or interaction. It’s very interesting to do that, particularly to an older woman. I understand that it’s a lovely compliment in a way, the framing of what I’m asking them to do, how I’m engaging with them. “Hi, I’m a photographer, I’m an artist and I’ve noticed you—” This kind of thing allows me to be complimentary but not in a sycophantic way. It’s just, “I saw you, I love what you’re wearing, or how you carry yourself or your attitude, and I’d like to try and put that into a picture. But it’s not a portrait of you, as such.”

And this is where the smartphone comes into play because where I used to have to explain all this to somebody I’d stopped on the street, and it all seemed a bit abstract, now I can stand there and show her what it is I do. “This is who I am. Here are my pictures, that’s what they look like.” So people have a sense of what I’m asking of them. And then they feel safe. They feel it’s a collaborative project rather than “I want to photograph you because there’s something weird about you.” I don’t want them to feel that discomfort.

Is it just as important to you to concentrate on women as your subjects today as it was twenty years ago?

Yes, absolutely. And it’s pretty simple why: I am one, so naturally I have a fundamental connection. Though I’ve noticed that over time a lot of my pictures have gone into single characters. And then the relationship between me the viewer and them is much tighter. There is something about putting more than one character in a picture that opens it up and you get a different reading. It depends where you put them on the plane of the image and how much attention you give them. In my pictures, the characters jump sizes, you know; there’s no continuity in the size of the figures, so that alters where the viewer finds the narrative. It’s a different kind of investigative process.

The pictures—particularly the more recent ones —are made up from so many different layers. Has that construction process, the building up of an image, become more complex.

Well there is something lovely about trying to keep an image pure… that mythical truth of photography. But that’s not really where my work is at, or what it’s trying to do. I’m creating an image more like a painter would create a painting. You can’t always get it in one frame. The picture I want is in parts, and I piece them together in my mind’s eye. Technology allows me to translate it into a final image. And as you become more influenced by technology, more used to Photoshop, your brain begins to see in a different way. It begins to grab bits around the photograph for the photograph, so it’s not a complete record any more.

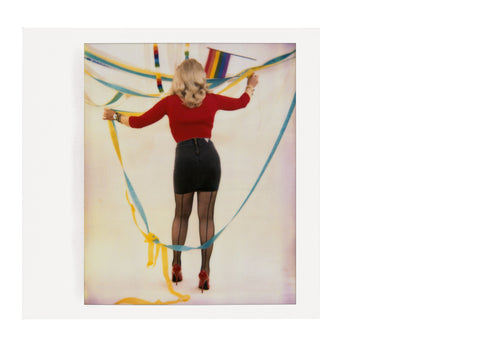

There’s a very recent picture I did at the Women’s March in Trafalgar Square last March. There’s the National Gallery with the hoarding and the flower in the picture was slightly further up, so I brought it down into the frame. It’s those little things. You don’t change what people look like. But we’re no longer constrained by the physical geography of a situation. I can see the image in my head so I shoot elements for that image, whereas before I would maybe pre-plan the image and then set it up. I’m interested in the psychological truth more than the photographic truth.

In your earlier pictures you often hired models to play the female role in a scenario that you had seen then wanted to construct in your own way. How much pre-planning do you still do?

Yes, I was casting according to the idea and the location. But I haven’t really hired somebody for possibly ten years. I think what happens when you start off making pictures like this is that it’s a big production, but as you learn how to do it, in a way, it just streamlines right down. And there is an element of serendipity in it, too. You can think of an idea or an issue that you have experienced or observed, and there’s something about mulling it over in your head that begins to attract, and it’s probably because I’ve just turned on my receptors.

I think first of all I was finding out how to do this, and how to create my own language, and it was very labour-intensive. It is just so not labour-intensive any more. And also, maybe because of the internet and digital cameras, it’s a lot easier to get someone on your side. Whereas hiring an actress was a way of ensuring that they would turn up. It was a professional contract, and they were quite happy to project themselves into scenes.

A lot of women today, particularly because of social media, are already very aware of how they look, so maybe they don’t mind being spotted. So if somebody comes and says “You look great. I think it’s a much more common currency, because everybody’s taking photos, of themselves and everybody else. It’s a much more common language.

It is a common language, but people are also more suspicious of why they have been picked out because there is so much exploitative stuff going on online, people are more savvy. Which is good; I think there’s more awareness of what can be done to a picture, you know, you want to know what your image is being used for.

I never ask to photograph the person there and then unless it’s an amazing picture that you just can’t miss. Generally, by the time I’ve caught up with them, I can’t breathe, and there is a kind of a vulnerability on my side, And there’s something about that vulnerability and honesty that also transmits. And a relationship develops. I give them the information about who I am and then they can go off and make up their own minds and they can do some research online. And with that, no one has said no, because they can see exactly what I’m talking about

Maybe women respond to your pictures because they recognise something in themselves or in other women. To some degree your pictures replicate that habit of women looking at women, of women evaluating women. So there is something familiar there, but it’s not like looking at a snapshot and it’s not like looking at a magazine portrait.

No, and I am not relying on the subject to tell the story, either. The story comes from what’s around her. Or maybe from what she’s wearing.

But don’t you want to suggest something deeper—a woman’s happiness or a woman’s alienation in a particular environment?

Yes… every time! My pictures are built on emotion. Every element is designed to drive the emotional IQ of an idea and trigger empathy in the viewer. I could give you an example from an early picture. The woman in the café with the fish mural on the wall. I saw the location first and found it to be a space of contradictions. There was movement in it with nothing actually moving. And at the time I was thinking about how when women were photographed on their own, in solitude, they were seen as lonely, rather than just being on their own. This was especially true for older women. So that location inspired me to explore the differences between solitude versus loneliness.

How much do you use your personal experiences in your pictures?

My pictures are definitely about the common experience but of course I am projecting some internal thoughts and observations from my own perspective. Some experiences that I’ve had that maybe translate into a constructive picture. For example, The Company of Mothers, a show I did at Tanya Bonakdar in New York in 2009. That was just me thinking about the women who in one way or another I have known most of my life. You try and make a picture that has the everyday and the accessibility to it, but is also somehow heroic. I think that’s what I was trying to do with those pictures. But I wanted to keep the women grounded in scenarios that would be normal to them.

There’s something in one of those pictures I’ve always wondered about. It’s the picture of the woman walking through the snow with her shopping on the pole. It could be read as being about the burden of motherhood, almost literally a yoke. Though, taken from that angle, she does look quite heroic, marching through the snow.

Well that’s a mother I know from my daughter’s school. She’s a very strong woman.

She’s also a black woman, and I wondered if you intended any observations about race? Was that something you wanted to emphasise?

The double burden? I actually quite like that in that picture, because it produces a tension in the frame. But this comes from a scene I’d seen probably about 15 years ago. I’d seen a woman carrying all her shopping on a pole like that, and I loved the shape of the figure.

So sometimes it’s literally just the graphic shape of a picture, or the colour that starts a picture off?

Yes, an example would be the girl with the pink hair. I had been thinking about the first moment a women realises she is pregnant. It can be a mixture of shock and wonder. Both your mind and body will undergo change and I wanted to reflect this in a picture. When I saw the girl with the pink hair go by on a bus in Shoreditch, I ran after it and luckily she got off at the next stop. It’s amazing that just with a brief glimpse of her, I knew she articulated that sense of change from one state of being to another. I think it must have been the way the pink drained in colour as it got closer to her head. Visually it denoted a metamorphosis.

So the hair is a metaphor?

Yes.

You belong to the generation that moved from analogue to digital. Has that made any appreciable difference either to how you work, or to the pictures you make?

Well, first of all, the process isn’t that much different because one of the biggest challenges for me, the most exciting challenge, is to see something in the world as it is and to be able to distil the essence of that scene by make a picture of it. So what I started to do with Photoshop is bring in that layering to images that are ostensibly just caught, really. Mostly my interventions are specific and strategic. One of my first photographs shot on a digital Hasselblad, is a good example. I did a lot of work on that image, but the final result isn’t that different from the original at first glance. But look more carefully and I’ve changed colours and intensities of the light in the crystals to try and force the eye to weave through the image before finding the woman in the frame. I wanted the complexity of those crystals to seduce the viewer into constructing the picture in their mind first. I suppose in a similar way to how a re-toucher works zooming into the individual pixels of a file.

I have certain motifs and textures that I like: something that goes from abstract into figurative, and if it’s a narrative story, then it’s quite nice that it has all those sections brought into one picture so that it has a sort of realism to it.

I suppose the question is: how much you can add or remove from a picture and yet still retain a sense of familiarity, the sense of “in the world-ness”?

A photograph is about the choices that you make. Now those choices aren’t limited to the moment you release the shutter. And I suppose after years of practice, I know what makes a better picture. And now I have a whole lot of powerful tools to help me.

But those tools can either enhance or distort the image. How do you retain any sense of reality, or does that become less important?

When you work with photography and have women as your subject, you are constantly asking what is the space between a mediated reality and the actual reality. And I think we’re at the point now in the digital revolution where the image is king. The image is the currency we work with—the picture-perfect selfie, the personal profile image, all that. In a way photography seems like 20th century technology but it still shapes us from a very early age. It gives us a subliminal language that we’re very sophisticated in. I think Instagram has really educated us in photography, too.

But do you find it a threat that everybody is making pictures all the time?

Well, one would think so, but I never get tired of looking. It’s a very bizarre thing. When I talk to my teenage daughters, they might make a comment if we go past something—because I’m always pointing things out to them—they’ll go, “That’s an Instagram picture!” So there is already a language established for an Instagram picture: it is the best picture of that event, that beach, that sunset, and it’s working to a preconceived idea of what that should look like. We’re all going the perfect professional picture, referencing something that’s already in our heads, a fixed referential. We make it as we think it should look like. When they say it’s an Instagram moment, they already know. It’s feeding into that stereotype.

But you are making pictures for the wall… how does social media affect them?

Well they’re still based on observation; that, mixed with the internal conversation. And the internal voice has become much louder because I have more experience of how images of women are used in the world, and I have teenage daughters who are absorbing all sorts of images. Even though they’re very savvy about understanding how an image is made—whether it’s been Photoshopped, or perfected or stretched or… that kind of thing, they’re still very influenced by them, and the bottom line is the final image, and they are so seductive.

The same type of images are shown to young women again and again, so it becomes a very limited visual language representing what it meansto be female—and we are probably subjected to it from about the age of nine. Yet there’s no education about this in any of the schools, no mechanism set up to teach young people how to deconstructand defuse the power of these images. And if whatthey are referencing are all those picture-perfect images, then we know that the discrepancy between the virtual life and reality can cause depression, feelings of inadequacy, all that.

It seems to me they’re trying to mediate between the two languages: girls are trying to find a way out of a landscape that is hyper-sexualised, self-objectifying. But appearance has become so extremely important. I am trying to educate my own two teenage girls! I really think that visual culture is the last battleground for women’s equality and freedom.

We’re talking about the kind of images that young women are exposed to on social media, but older women aren’t immune—I mean, how much do they affect you?

As a middle-aged woman now, I am absolutelyamazed that I don’t feature anywhere in our mainstream visual culture. There aren’t any pictures that I relate to as an older woman. What am I supposed to do, just disappear? If I’m not on the visual landscape, then I have no currency. But If they are obsessed with selling youth, they are not going to be using a 46-year-old unretouched woman. I think we’ve lost perspective. We’ve got so used to always seeing that same type of young woman, whether she is advertising pizza or Gucci. There is no cross-section. I suppose that’s what is affecting me. And I would think all women even if they haven’t thought about it.

My daughters, when they were in year nine, year ten, in school, they were shown videos of what real women look like because they don’t really get to see that very much. So they were shown a naked thirteen-year-old girl—the same age as them—and my daughter said there were a few comments like, “saggy boobs” that sort of negative comments. Girls are very self-critical: they’re taught to be. So you can imagine what happened when they were shown a 40-year-old woman’s naked body, apparently there was an audible gasp that went throughout the whole classroom, like, Aaaargh! And this was just a normal unretouched body, because they never see one.

If we’re not valued in our visual culture, then are we always undermining ourselves? I know Liz that you and I are women who accept the issue of ageing, but deep down is our value still on how we look? Do even we have unachievable expectations? How many times do women try to conform to an idea of a younger women because they think that equates to “success”. And men do it as well. My dentist was saying how many fillers and Botox jobs they do for men in the City, because they work so hard they burn out so quickly, they look like shit, and yet their currency is still in their perceived virility.

I realise that the obsession with youth has probably existed since human history began. But if that’s the case, I’d like to know more about how those middle-aged women are feeling about being undermined on every level. They’re not young enough, they’re not sexy enough, they’re not slim enough: they haven’t aged well enough.

The trouble is, a lot of women want to be seen the way they looked twenty or thirty years earlier.

And that’s because we don’t see another model. We are operating from the same model we’ve been operating from since advertising began. And we’re still making physical judgements about ourselves and other people.

When I photographed Naomi Klein for the Financial Times, I looked at the images that had been taken of her already and they were all very much about what she looked like and not what she stood for. When you’re reading an article, the image is the first thing that you see, the first information you’ll register. And images of women of a certain age are so carefully scrutinised. So rather than doing a Vogue-style image, how do you create an image of her that stops people from turning the page but doesn’t allow them to be critical; which forces them to work with their own creative abilities in deciphering and enjoying a well-made photograph that tells you more than what she looks like, or how well she’s aged?

We are still setting standards that we try to achieve, and that we judge other women by. And it’s really pernicious, because it doesn’t allow for women to be different, or themselves, or not to conform. They’re told the same thing over and over and over again, from social media to click-bait down the side of the Daily Mail site. This is the final frontier. Because I think there is a commercial imperative to subjugate women, or to make us feel insecure, so we will buy more shit. And what happens when that collapses?

But how do you respond? Does it make you a more political artist in what you produce?

Well it’s not protest art…

No. But if you have the power to put something on a wall, you can make work that engages more overtly with these subjects? Or doesn’t it come out like that?

Not in my work. Because even though the women in my pictures are subjects, rather than as specific women, I still find it very hard to project on to them something that’s individual. I make pictures from women to find some kind of connection with that doesn’t actively need them to take a stance. My pictures come out of a sort of defiance against the kind of image that’s too easy to read about a woman, that either overtly empowers her, or exploits her. In lectures I give to undergraduates I call it New Visual Intelligence; I want to encourage an understanding that we need to construct a new way to represent women. We’ve evolved to decipher images over tens of thousands of years, but in our own lifetimes the image has risen to become the main form of communication… and we mustn’t be stuck with the myopic visual language devised by grey middle-aged white men who think far too much of themselves. Us women must take control.

Students see my work a lot, probably at their B.A. stage, and the majority of them are women, and they find something in it that expands their experience; something that resonates, that stays with them. I think there is a kind of empathy in the pictures that people respond to and it does create a space that demands a different type of interaction from you as a female viewer looking at the subject. I am trying to find another way of photographing women that doesn’t require them to be active, sexy, naked or empowered. This whole empowerment term is really hard to get your head round because it implies you have to behave like somebody else, when most of us are just human beings moving through our lives,

Is that something you can imply in your pictures?

Well I can give an alternative. I am sure that if you were to think of what women look like now, you’d either have a skinny model or Kardashian, but there has to be something in between, something with more depth, which demands more engaged, active looking than just the mindless consumption that a lot of those images are playing to.

I photograph women because I want to see different types of images of women out there rather than the same thing. I’m interested in how women are represented in the world because I worry that if there’s a very narrow idea of what women are, we might not be able to reach our full potential. And our daughters might not reach their full potential, either.

Of course, we’re all so individual, from different backgrounds, with different experiences. I can’t speak to “all women”. I try to speak of the collective experience of women with my specific language, the way I see, my signature style for lack of a better word, to put something else out there.

Can I ask you about narrative? In the bid for conceptualism in photography, narrative became a dirty word. But it still seems that your pictures, in part, are narrative-driven.

It’s way more the narrative influence. It’s telling the sort of stories that might seem insignificant, but by photographing them in a particular way you make them more significant. But they still have to be relatable. I’ve noticed with photography recently that the images are illustrations to the ideas, to the concept, and I think that’s fine, but for me personally that’s never the case. So it will be constructed, yes, but it’s not illustrative of something else. It’s the narrative that is already in there. So the question is: conceptually, how do you build narrative into a static image?

Do they always have to have a figure in there?

Well, mostly for me they do. And nearly all these women probably have some connection to me.

So does that mean you feel you can’t portray women of a different ethnicity, or women from a different culture?

I look at these pictures and I think, why are the majority of my subjects my ethnicity, or look like my ethnicity? It’s probably because I have never experienced life as a black woman or a woman wearing a hijab. I don’t completely shy away from casting women from other ethnicities because we share the common experience of being female in this world, but I can’t appropriate their specific struggles and it might look as if I’m trying.

You’re worried that the viewer would read your intention as having photographed her because she was black, rather than because she was a strong woman? You don’t feel confident about that?

No, of course I don’t feel confident.

So that’s why you don’t do it?

I’m aware first of all of my white privilege. I know exactly what that means, and I am wary of trying to take somebody else’s platform when they know what they’re talking about. If people are given a platform to express their own feelings and their own experiences, then I don’t feel that I can be a surrogate for that now. But I will get over it, because otherwise I’ll end up in the other place where I just have pictures of white women.

But what about this picture, of the woman and the boy against the wall? It speaks of being a mother, yes, but doesn’t it also suggests something more?

This one was a really informative picture for me, because this woman here with her son, and I had the best conversation about raising a son in Hackney. They were both waiting for the bus, and I saw the wall and the bus and asked them if they would do it. And you know, after a certain level of suspicion initially on their part, we went on to having a really informative, deep conversation about raising children and the real danger of knife crime they confront. And when I sent her this picture, given what we talked about, she really loved it. And the thing she loves, actually, and what I love, too, is just her embrace of her son and that’s not specific to him, it’s the emotion a mother has for her child, any child.

Isn’t it also about what you talked about—about how does she keep him safe?

But he’s still a child.

Yes, but there seems to be a tension in the embrace. Soon he will escape it. And there’s a visual tension, too, between the human figures and the narrative—the narrative playing out in a static frame, in the colour and shape of that wall…

There’s so much of it that is unconscious. You can put that down to luck but probably your brain is making those connections the whole time. What was very important to me about this picture was her response to it, you know, that even though you couldn’t see her or her son, it meant a lot to her what it was communicating. It was an emotional image because how I talk to the women that I’m photographing is on an emotional level. For some reason we can get very quickly down to the nuts and bolts of our lives.

I sometimes think that a lot of these pictures are just records of meaningful exchanges in a way, and being creative with another person. I didn’t tell them to embrace. I didn’t tell them to stand like that. But people begin to get comfortable in the image and they do their own thing.

You’ve spent the past fifteen years as a working mother—how does that affect your work?

I work a lot less. [Laughing] And I probably should feel guilty but I don’t. I’m always making photographs, thinking about them, writing about them; it’s self-generating. I never stop taking photographs. I might not carry this heavy camera around with me. But if I walk into a room I’ll frame it up immediately. I have pure pleasure in the act of making a photograph. It’s automatic even without a camera.

What I love about photography is you can be many different types of photographer and avoid categorisation. You can work as a photojournalist, you can work in fashion, you can work as an artist. Each of them have their ways of performing with the camera. You can make something that’s labour-intensive, very layered, full of meaning, that you’ve set up and you’ve cast and you’ve lit, and you’ve done all that to. Or you can be just as free to go out with your camera and photograph a scenario you’ve seen on the street or you can do something in between, where you see a location, and you know how it will abstract itself and you can cast it there and then. There is no single way of doing it.

If you’re always switched on as a photographer then it comes in many different ways. At the end of it there is a need to communicate a love and frustration that I feel for women and photography and that’s why my pictures come out the way they do.

There was a time when women photographers would insist “I’m a photographer, not a woman photographer”. But it seems to me you’ve gone the other way.

When I was a young photographer, I didn’t see why I should be defined by my gender, but then it became really important to me to take my position as a female photographer with a female perspective. Up until my mid-twenties. I didn’t see why it was necessary, and then suddenly I did. I thought, yeah, absolutely. If I’m going to become a talented photographer, well that’s where I’m going to put my talent.

You know, from starting out seeing endless lists of male names for awards, for books, that kind of thing, I’m so excited now to see how the landscape is changing and the generation of young women who are changing that. But I just want to make sure that they change it for the long run. This isn’t another flash in the pan. When I was twenty-seven I got a lot of attention, and I got a lot of attention for a lot of different reasons, and that’s almost what this book is for—is to make the connection between my generation and my experience to the next generation. I’m not telling them all to go off and be female photographers, but they do have to be aware of the language they’re contributing to; just to realise what’s gone before, to not have an amnesia about what we’ve all experienced, and to see it having value, and not to dismiss it.

Edited from conversations between Liz Jobey and Hannah Starkey in London, 2018

From 'Photographs 1997-2017' by Hannah Starkey, published November 2018.