Many of the pictures in this volume are already in the children’s family albums. To the children and their families over the years they will summon up associations, details and stories — a continuously self-revising stream of captions. We can only read the laconic literal titles here — “My daddy feeding the cows,” “My foster family on Turkey Creek,” “My mother feeding the cat,” “My sister’s baby’s funeral,” “Mamaw and the baby” — epeat the words, and point to the beauties of the photographs. But in many cases, if we take the captions away we are speechless, as if in the presence of a mystery.

Many of the pictures in this volume are already in the children’s family albums. To the children and their families over the years they will summon up associations, details and stories — a continuously self-revising stream of captions. We can only read the laconic literal titles here — “My daddy feeding the cows,” “My foster family on Turkey Creek,” “My mother feeding the cat,” “My sister’s baby’s funeral,” “Mamaw and the baby” — epeat the words, and point to the beauties of the photographs. But in many cases, if we take the captions away we are speechless, as if in the presence of a mystery.

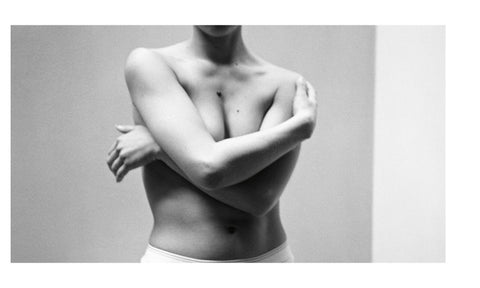

Considered as pictures without titles, many of the works here strike us as explorations (or études) of their subjects, pictures of things seen, arrested and held up for contemplation — not reports but fantasies, and not literary fantasies but visual ones, variations on a motif, especially on the motif of the human figure, figures which are often strange, slightly off, yet rendered with such apparent precision and control that while they are clearly photographic transcriptions of appearances, they have the singularity and surprise of quick, sure inventions of the artist’s hand, improvisations, drawings, not observations of what the body looked like but proposals for what it might look like.

In some of the most fantastic pictures here children hang upside down from trees, from sheds, and from ledges in the hills. The captions tell us that these pictures represent episodes from dreams — the most private texts and visions that Ewald asked her pupils to illustrate.

These are scenes of flying, of falling, of floating, of being pursued by creatures from outer space, of being attacked by toys or captured by dolls and absorbed into their world; of killing one’s best friend, of watching one twin kill another and be haunted by his ghost. To see Wendy Denise Caudill pose as a bride with her kid brother as her groom, to see Denise Dixon’s naked mud-daubed brother is to have the sensation that we look directly into the photographers’ unconscious.

“I dreamed I killed my best friend Ricky Dixon,” writes Allen Shepherd. In Shepherd’s picture a boy, his face pale with winter light, his eyes closed, slumps forward as if hit from behind, and falls into the fork of a large tree. His arms are outspread. His body is in the crotch of the tree, as if between two thick legs. We can read the picture in terms of birth and crucifixion — pictures as deep in the unconscious as murder, yet perhaps not retrievable to Allen Shepherd because not admissible, although present enough to us.

And if you look hard at Ricky Dixon’s face or at the face of Scott Huff in his flying dreams, or at Denise Dixon’s little brother as he holds the tombstone and screams in the vampire dream or at the girls who fall and float, you will see emotions and fears that are broader than either the picture or the caption warrants, nameless, and elemental.

And they are not that much more exaggerated than the anxious looks on the faces of the women in church, or the grin on the face of a butcher with a severed hog’s head. The line between the dream pictures, and the portraits and the photographs of daily life, is thin. The miracle of these photographs is that while the children map their inner worlds they are also our guides to the material culture and daily life of the hollers. We understand the children’s work as a collective document and communal history, and the children as the hollers’ chroniclers and scribes.

The children understood the photographs as chapters of family history, as artifacts uniting the generations. In Diane Fields’ picture of her family, there is a framed portrait of Fields herself; she put it there so that she too would be present in the family group.

There is no doubt that the children knew themselves to be making documents. Ewald asked the children to photograph a day at school as an exercise in analyzing, expressing and recording something at once so complicated, public and objective. In 1977, when the children were preparing the work for exhibition in Chicago and New York, they decided that they had to photograph the mines and the land the better to “explain” the place to outsiders.

Yet how public a sense of the documentary did they have? They were not primarily interested in the structure of communal life. They did not photograph the towns or the roads connecting them; nor did they photograph stores, gas stations or other places where people gather, except for church.

Their world is intimate and still. The places they describe are self- contained; no fragments of details along the edges of the pictures imply connection to a larger world just outside the frame. Here time is slow, bound to custom and the change of seasons. Parents are affectionate but not sexual. From where the children stand, adults seem large even when they are not so near. Dolls and pets are close but not larger than life. Where backyards merge with saplings and underbrush, the small and knowable thinly wooded foothills still look like forest, and beckon. The children see three stages of human life — childhood, adulthood and old age. They do not photograph adolescence — indeed, every one of them stopped taking pictures at puberty — thus the time that most immediately awaits them is held at bay, and the pace of this work seems slower still. Depicting neither advertising signs nor automobiles, and giving cursory description of mass-produced objects (ready-made clothing, for example) whose style would summarize the times, this collective document is largely dateless. The moments it describes occur in emotional not historical time. The children’s Letcher County has something of the remoteness of myth or of those ballads whose action occurs in a far country ruled by a nameless lord.

Yet how full their realm is of life’s clutter and informality: a coffee cup left precariously on the back of a couch; untied sneakers; awkward kisses. When Ginnie Walters photographed “My Foster Family on Turkey Creek” early in the morning, her little sister stands in the dusty yard still wearing her white fluffy bedroom slippers. We feel that we are in the hands of good photographers because they keep surprising us. Their appetite for pictures and for the way things look in pictures is large and delights us. As they lead us to what is beautiful in the commonplace we accept them as trustworthy guides to the hollers, and they enlarge our sense of what a document can contain. To take a stance that says “These things must be photographed — preserved and remembered” is to act, intentionally or not, as the conscience of a community.

Yet how full their realm is of life’s clutter and informality: a coffee cup left precariously on the back of a couch; untied sneakers; awkward kisses. When Ginnie Walters photographed “My Foster Family on Turkey Creek” early in the morning, her little sister stands in the dusty yard still wearing her white fluffy bedroom slippers. We feel that we are in the hands of good photographers because they keep surprising us. Their appetite for pictures and for the way things look in pictures is large and delights us. As they lead us to what is beautiful in the commonplace we accept them as trustworthy guides to the hollers, and they enlarge our sense of what a document can contain. To take a stance that says “These things must be photographed — preserved and remembered” is to act, intentionally or not, as the conscience of a community.

Excerpt from 'Record of a Summery Immagination' by Ben Lifson, from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald, published in August 2020.